- Home

- Segoy Sands

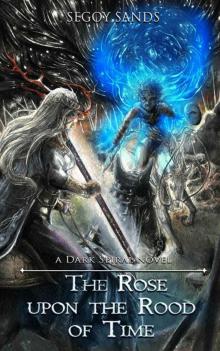

The Rose upon the Rood of Time (Dark Spiral Book 1)

The Rose upon the Rood of Time (Dark Spiral Book 1) Read online

The Rose upon the Rood of Time

Book One of the Dark Spiral

Segoy Sands

For ZSO and TDN

Red Rose, proud Rose, sad Rose of all my days!

Come near me, while I sing the ancient ways…

William Butler Yeats

Copyright © 2014 by Segoy Sands

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0-9768265-6-9

from the Annals of the Airgid Ardaigh

In the cave temples of ancient Sanskra, the thousand-fold sisterhood gathered around the all-compassioning Jivana, the seven-eyed, who guided them in the stages of the dissolution of the coarse body and mind. Never had there been such a garden of peace, where violence found no root in human hearts. Trees and flowers abounded there, and many sweet singing birds, and countless gentle creatures, so that it was called the sweet land.

Rumor spread north and west across the sea to Aina Livia, to the court of the Wynfyd Lárach Dain, who sent three vessels of cindoor and madeira and deodar, laden with splendid gifts, to invite the Jivana to her land. Well pleased, the Lady sent the seven Süleviae, each with thirteen adepts, back aboard those lovely ships. With them, it was said, they brought the airgid ardaigh.

Their coming brought joy to Lárach Dain, for they spoke as seeresses and told her that the daughters of her line would open the gates of paradise. Gladly she gave them La Tiërra Rosa for the building of seven temples, and promised them the babe that was in her womb, which many portents showed would be a girl.

1 MOONLESS DARK

A cacophony of raucous rooks gyred, like a lax and intermittent filament, over two minuscule figures, a boy and ox drawing a plough on the shoulder of a mountain. Northward, a legion of slouch-backed figures heaved upwards, the ten thousand giants of the Greenmen, carved out, long ago, by the slow knife of a great bluish slurry of glacial water.

Tilted up toward the noisome birds, the boy’s face wore a philosophical cast. His body was attuned, despite the riot overhead, to the slow time emanated by those massive mountains, whose traceless depths absorbed all transitions. The Bedes of the Aurum said the Greenmen were formed by mineral changes too subtle and too slow for the eye. He favored the tales of his own folk, who said they were half in this world, half in the Nog, the borders ever shifting, so that one misstep led out of time forever.

His name was Arryn Dunlan. They called him Wren because he was small, but apart from size he had little in common with that euphonious little gray visitor. In point of fact, it was hard to get a peep out of him. His mother Lorca and sister Boinn made diligent propitiations to the lugh, but the fount of speech bubbled up late in him, and then ebbed. Maybe he had too much of the north in him to trap the world in words. Or maybe he spoke so little because he had never been given a say. One by one, the other men of the family had left - first Cole, then his father, then Dillan - leaving him nothing but toil. It fell on him to work with Horn, in silence and solitude, letting the faithful old ox follow a lifetime of habits, drawing grooves in a landscape too vast for human concerns.

His home was a crannog in the bog lake, prone to damps and vapors, and to ill humors some might say, but peat fire and experience with wood and stone passed down for generations kept it snug. Against the moaning winds, it had the shelter of bulrushes and marsh trees. And, out in the plough fields, where Wren and Horn had paused, his father’s windbreak - poplars, lindens, ash, and spruce - formed a ragged line of pikemen, braced against the shapeless onslaught of the air.

Now and again, the trees would bend and shake and splinter under the press of that unseen host. But it was warm and windless enough in the crannog, nestled below, its quiet wisps of peat smoke indistinguishable from the marsh fog. If one looked carefully, one could see where Rufus had added stone and soil and sod around the islet, which jutted into the water like some runic key, ringed by stout poles and connected to the bog-land by a wooden causeway.

Across the causeway, a footpath led through a wood to a bridge that spanned a purling brook, out into pastures, and into the fields where Wren, the first pass done, was unhitching Horn. At a twisted cottonwood, dark limbed and green-tipped, he tethered her, patting her wooly curls. A mystery before words glistened in the animal’s dark eyes, reminding him of the Radda, which Lorca had made him begin translating last winter. It was an old book, heavy and precious, its engraved leather cover binding two hundred vellum pages of neat black ciphers and crushed-gem illuminations grown brittle and yellow at the edges. Looking into Horn’s eyes, it vexed him, that one verse he could never quite get right:

Ask of the owl in the moonless dark

What riddles in the old oak’s knot

What hides under root, leaf, rock

What, warp and weft, is perning

In the hollow horn’s turnings.

Open the eye of the heart.

*

A brook passed through Durness, one of many rivulets that fed the Turquoise and the Ololon, but large enough to merit a bridge of sorts. One path from the bridge led to the fields. Another was marked by a cuneiform of wedged hoof prints leading upstream to a white-braided waterfall, where a herd of podgy sheep nibbled meticulously at damp rock herbage. Their shepherdess, a lanky girl with dreaded hair, waded under the mist-spray with a long spear. This morning, metal trout flashed gold and silver in the pool, which roiled with tiny whorls. Speaking thus, in signatures of living beauty, the world seemed to be telling her that she was right where she belonged in its patternless pattern. But it was saying something else to the dogs. They were frightening the sheep into disordered sallies up and down the bank.

“Shite between the shaggy ears!” she upbraided them, but they yelped on, nipping at the sheep’s flanks, too stupid to know they’d caused the whole commotion in the first place. She wondered what had set them off.

“Sridean! Taibreamh!” They looked at her meekly, drooping their doleful ears, and ran to the river’s edge, jowly masses with lolling tongues. Both took a few steps into the current to lap the water, alert to the gleams of darting fish. Taib crouched low, as if to catch one, but then lifted his ears and turned toward the crannog, whining. What was it?

A hope that father was back, if only for a visit, leapt into her heart. He’d be saddle-tired but smiling, wrapped all in fur, red beard all tousled. He’d say Cole was coming home soon. Or, Cole might be with him. Curse them both. The line in the middle of her palm sloped downward, but she wasn’t a dreamer, not anymore.

No, it wouldn’t be father today. Someone had come, though, the way Tai and Srid were carrying on. She ran along, barefoot, with the dogs and the flock, down the steep trail to the river bridge, which Rufus had hewn when she was seven years old, letting her ride Horn’s back as the old ox hauled the trees. Now, the sheep’s hooves clattered over the planks like drumming rain, eyes bulging, necks leaning forward, eager for their pen. They put great stock in the two big dogs’ noses and ears, and would gladly go without food rather than be food. Even after they were penned and nervously huddled in the shed, though, the dogs were restive, insisting she follow — running ahead, looking back, barking. They were heading toward Wren in the twin brook field.

*

Father left them five years ago. There’d been high tension over sending Bóinn to Anve, the minor spiral to La Verai, the Green Lady. One could learn and serve at Anve with little binding obligation. The greens were unceremonious and nonchalant, and Anve, at the southern edge of La Tierra Rosa, was a place of subtle beauty, where ochre desert met a slow wave of blue and green. Lorca introduced it as a possibility, a practical issue. Boinn had no sisters and needed to learn from ot

her women what it might mean to enter training, she said. Her tone was calm and considerate, and Rufus made no reply, but a silent struggle seemed to be passing between them. Not much later, Rufus left.

Wren did not see his father again until mother sent him to Twill with Cole, when he came home from Wisp, for a match between Aegle Klaast and Luch Klaast. They’d had a lively time around the dinner table. Cole looked leaner and harder, tattoos covering half his torso and part of his jawline. Lorca teased him about being a ladykiller not a man killer, and he’d still acted the boy, making Boinn blue-faced with anger, and razzing Wren about the cwlwm aer.

“Make a run for it, wee bra’, before ma and da send you to the Bedes.”

“Shut up!” Boinn scowled. “They’d never.”

“Boring and corpulent and flatulent,” Cole said, “and they use young boys for favors.”

“And you know that how?” Boinn inquired.

“Ask Keene,” he pursed his lips, widened his eyes, and nodded knowingly. “Am I right, ma?” When Lorca smiled benignly, he went on, “Get word to me if ma and da try to make a girl of you. I’ll take you up into the Greenmen myself, to see if we can find those floating holy men.”

“Well, you won’t,” Boinn informed him. “Men are clods who can’t feel the wind, let alone untie its knots! And when have you ever even been in the Greenmen? There’s feral markings in the trees and stones, a thousand times fiercer than those silly inkings on your arms.”

“You’d know,” he grinned, winking at her matted hair. “Me and Wren, we don’t plan on joining your hairy folk, though. We’ll just go have a look-see.”

“They’ll cook Cole in a pot and make you watch them eat him,” she told Wren. But no sooner had the words come from her mouth than Cole had her in a headlock. “Now this one,” he said, rapping his knuckles on her knatty head, “is the one you should have sent to Cogan, not Dill.”

After dinner, Cole took him up to the Bol Braster, the only real inn in Twill, to pay a visit to their father. Cole was quiet during the ride, and did not speak until they neared the town’s lights.

“He’ll be bringing you to the klaast tonight. Do you miss him?”

“Yeah,” Wren breathed.

“Well, you don’t talk much, but you speak no ill of anyone, do you?” Cole mussed his hair. “He’s a bitter old bastard. He left you and Boinn on the farm with ma. That’s just shitty. And for what? To hang around with Dagda, rubbing heads, longing for people to say their names again. Dillan and me, we’d come back if I we could, understand. We can’t. We have to find our way now, and so do. Keep being strong like you’ve been.”

Cole left him at the entrance to the inn, watching to be sure he actually went through the doors to meet their drunkard father. The main thing Wren remembered now, three years later, was the old man’s weathered hands. He’d been running his fingers over a high-wrought cup, where a fleet of copper ships sailed a silver sea through an inlaid turquoise map of the hundred isles between Old Epona and Aina Livia. The inn was dark, with quiet black tables where men could murmur in silence. It smelled of oil lamps, meat, and beer. Outside, in the oak trees, a great horned owl hooted mournfully. His father set a tankard in front of him.

“We’ll go see Cole,” he muttered.

The owl hooted again. To the terrified mice in the marsh grass it must have sounded like the hollow voice of a death god. Wren imagined being that mouse, searching for some hole to hide in. Rufus refilled his cup. “Your mother wants to send you to the Aurum. To let you be with books, lad. Half the knowledge of the world’s in books, aye. You’ve a cousin in the Aurum, too. And maybe that’s the way.” He took a long draught and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. His voice dropped lower, “The Aurum’s one way to learn more about the Blakes and Bedes. And as you weren’t born a big bairn, you’ll need to be clever as you can.”

Wren watched the men stooped over the bar and over their tables. They all seemed to shar a brooding look of violence and demoralization. Their eyes lingered too long on the barmaids that served them.

“Your brother Dill’s with Uncle Cogan. When he’s ready, he’ll join Aegle Band, like Cole. He’s twice Cole’s size and half the pain, and he’s been since the birthing bed, ask your ma. Now Boinn was born with the cord wrapped seven times around her neck, blue as a bird. And you were born in the worst lightning I’ve ever seen, forest fires down in the Ynon. Aye, Thoirni was in his cups and in a rage. I went to fetch a midwife, and by the time we got back, Lorca had you swaddled and asleep. Didn’t even feel it. Looked down, there you were. Still the quiet one.” He thumped his three-fingered hand on the black table. “She had you reading and writing before you could pull on your own boots.”

Rufus always grew voluble when he was troubled. Probably he hated the idea of the Aurum. Did he know how many chores had fallen on the three of them, since he took Dillan and left them the work of the crannog? Did he want him to leave sister and mother on their own? It all made no sense to him, but he knew it came down to the Sei Sí. Men who saw those times sat drinking in taverns. If you touched the ground enough, it made your hands sane, but those men seemed afraid to work, afraid to come back home.

Wren realized that Rufus wanted him there tonight not for his own sake but to help him play the part of a father in front of Cole. If anyone had troubled to ask, he’d have told them he wanted his bed, and was allowing himself a tiny modicum of hope that all the beer and talk would make Rufus too lazy to march out to Luch Klaast. But Rufus eventually stood up and told him to throw on his coat for the long walk on the south road. They walked in silence. Low clouds sealed the sky, and the forest and marsh bogs crowded in on them, so he couldn’t see more than a few feet ahead. But Rufus knew the way.

From outside, the rough-hewn roundhouse was squat and wide. At the door, a gap-toothed, gray-pated man, eyes lost in a maze of crowsfeet, patted Wren’s head, muttering, “Essger on you, Essger on you.” As he entered, a wave of stale warmth washed over him, smells of beer, arachuan, a strange meld of mellowness and aggression, sharper, more electric, and more fraternal than in the bar. In the torchlight, shirtless men leaned over a low balcony above the earthen ring, shouting softly and intensely at the challengers circling one another in the klaast, striking out like the lightning god Thintri with fist-metals, blocking like the thunder god Thoirni with forearm disc-shields.

Almost right away, he spotted Cole, who was nineteen, neither tall nor brawny, with laughing blue eyes and a blondish-brown beard. He was sitting by a fire, playing a cittan, the restless, thrumming chords leaping under his hands. He and father didn’t seem to see each other. Rufus made Wren keep his eye on the matches, as if Cole wasn’t even there, telling him the names for particular moves, sometimes scoffing at a blunder, but mostly deeply attentive, as if there were always something to learn, something important, something valuable. It all looked the same to Wren. Same moves. Same strategies. Same flow. But once a young bunder named Sieval, who hadn’t even made slag yet, moved in a way that seemed slightly out of joint. Wren thought he could see it, how time slowed down for the boy in the ring, and how, if you could look into the syrupy ripples where time slowed, he took many shapes, many possible forms. When the maor reached into a copper-colored bowl and picked Cole and Fergal, a grim, look came into Rufus’s eyes. Fergal was seasoned, maybe twenty-six, bald, lean, with thintris scored into his long arms. Like father, he’d been standing along the rails, with a keen eye on Sieval. But Cole, well he wasn’t even in the klaast house.

“Go and fetch your brother,” Rufus pushed him toward the door. “He’ll be by the firepit with his fool cittan singing his love songs. Be quick.”

The Eye gave Wren a wink as he hurried out into the misty night air. The fire was just out to the right of the building, with several men, and a few women and girls, sitting around, smoking arachuan and listening to Cole. The heat glowed bright and golden on his impassioned face, so that you didn’t even notice his hands on the strings, from which the clear

notes rippled like water in the desert. His voice was plangent and sweet, and as Wren came closer he began to make out the words:

Where may she be,

My spiraling lady

Deep in the fires of the dark

I’ll lay my head down

In the lap of the Lady

And bathe in this river of sparks.

For, there’s life in death

And there’s death in life

And a black wound in every heart,

Like ashes she poured,

When the sweet night was over,

Out of my cumbersome arms.

She went down to the edge

And downward she wandered

To bath in the spiral in the stars.

She went down to the end

Down my girl waded into

The river of sparks.

When the song finished, Wren tapped Cole’s shoulder. “Time,” he said. Cole handed off the instrument, stood, stretched, and took a last drag of arachuan. He put his arm around Wren’s neck, and they sauntered in past the Eye together.

“Go back to the old man,” he said. “But trust him no more than the maor’s bowl.”

Wren hurried back up to the railing with Rufus, and then Cole entered the ring grinning sheepishly, a half-hand shorter than Fergal, and half as convincing. There were whorls of thornis around his biceps and forearms, announcing his victories in klaast matches, and thintris to show his speed, but Rufus stroked his red beard. “Half the world’s knowledge, lad, is in getting your ass kicked,” he said. “This won’t be thintri-thoirni. See their empty hands? It’s a boxing bout.”

The maor shouted out the match and, for a moment while the two men were circling each other, Cole looked quick and limber. He threw shadow jabs and kept his feet moving, so that Fergal had to focus on tracking him, though once or twice he shot out an arm and landed a test punch from a fraction beyond Cole’s reach. Rufus said, “He’ll wait for Cole’s misstep.” Anyone could see that, but Cole took the bait, with a crisp jab that didn’t land, which opened him to a flurry of blows. Though a few men in the crowd groaned, more likely because they considered the match over than because they’d been rash enough to bet on the young clown, Cole managed to use his loss of balance to land a few wheel kicks. A good feint against someone less skilled, but wheel kicks were weak when they were telegraphed. Some of the men in the balcony shouted for more acrobatics. But Fergal had longer legs, and faster ones. One exchange after another, without excess, he gave more than he got. When the maor stopped the match, Cole was bleeding from mouth, nose, and arms. He limped away, and winked up at Wren.

The Rose upon the Rood of Time (Dark Spiral Book 1)

The Rose upon the Rood of Time (Dark Spiral Book 1) The Gates of Paradise

The Gates of Paradise The Gates of Paradise (Dark Spiral Book 2)

The Gates of Paradise (Dark Spiral Book 2)